Sponge bodies are diverse in form, ranging from encrusting sheets, to

volcano-shaped mounds, to tubes as small as one millimeter or as large as one

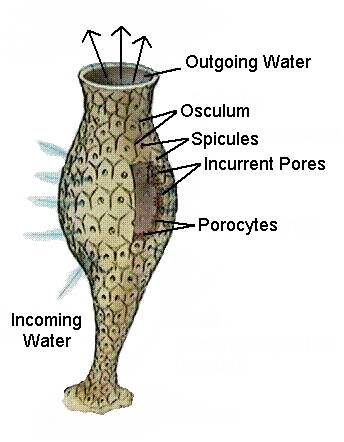

meter. In all cases, sponges have a canal system, through which they pump water. Water enters

through pores called ostia, flows through canals to a spacious chamber called a

spongocoel, and finally exits through large openings called oscula.

Often, sponges are distinguished by the level of complexity

exhibited by their bodies. The simplest form consists of a single tube

two cell layers thick. Sponges with this type of architecture are

necessarily very small due to surface area to volume constraints. In

order for a sponge to attain greater size, the sponge wall

must fold in on itself.

Like cnidarians (jellyfish, etc.) and ctenophores (comb jellies), and

unlike all other known metazoans, sponges bodies consist of a

non-living jelly-like mass sandwiched between two main layers of cells.

Cnidarians and ctenophores have simple nervous systems, and their

cell layers are bound by internal connections and by being mounted on a

basement membrane (thin fibrous mat, also known as "basal

lamina"). Sponges have no nervous systems, their middle

jelly-like layers have large and varied populations of cells, and some

types of cell in their outer layers may move into the middle layer and

change their functions.

Most sessile or slow moving animals on tropical reefs have developed

the means in which to produce a wide array of chemical compounds for

self defense or to prevent other organisms from growing upon

themselves. The brightly colored Nudibranch are a good example of

an animal group that not only produces toxic, defensive compounds, but

advertises that they do by being brightly colored. While many

sponges do not advertise their toxicity through colorfull displays,

they can and do produce some of the most elaborate compounds found

anywhere on the world's reefs. For many years now, science has

been collecting and analyzing a great many sponge compounds for use in

the medical field to combat human cancers and for their use as

antibacterials. It is also thought that many of these compounds

may be used by the sponges as a form of chemical warfare (allelopathic)

against other encrusting or encroaching organisms including other

sponge species. This is where sponges can become a real problem in our

aquariums should they feel the need to defend themselves or die and

cause the release of these compounds. Which could of course cause

the rapid demise of the other organisms we are trying to keep as part

of our captive reef ecosystems. A number of times I have

collected specific sponges with the thought of adding them to my

aquarium only to find that they had released some form of toxin while

in my collection bucket on the way home from our local reef which

promptly killed any and all other creatures that I had collected and

were sharing the same bucket. Over time and through trial and

error I have come to learn which types or species are not prone to

cause such harm and will try to include photos of those that I have

found to be suitable for collection and keeping within an aquarium.

Sponge bodies are diverse in form, ranging from encrusting sheets, to

volcano-shaped mounds, to tubes as small as one millimeter or as large as one

meter. In all cases, sponges have a canal system, through which they pump water. Water enters

through pores called ostia, flows through canals to a spacious chamber called a

spongocoel, and finally exits through large openings called oscula.

Sponge bodies are diverse in form, ranging from encrusting sheets, to

volcano-shaped mounds, to tubes as small as one millimeter or as large as one

meter. In all cases, sponges have a canal system, through which they pump water. Water enters

through pores called ostia, flows through canals to a spacious chamber called a

spongocoel, and finally exits through large openings called oscula.

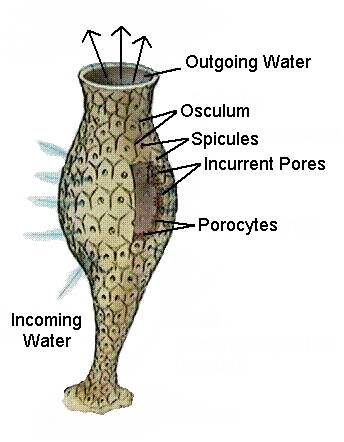

There are four different types of sponges from different

classes: Calcarea, Hexactinellida, Demospongiae, and Sclerospongiae.

They are split into the classes based on the type of spicules they

have. This is an important fact when considering the sponge

species we are attempting to keep within an aquarium setting as the

materials needed, such as silicon, will need to be present in its

dissolved form within the water in order for the sponge to create new

spicules needed for support during growth.

There are four different types of sponges from different

classes: Calcarea, Hexactinellida, Demospongiae, and Sclerospongiae.

They are split into the classes based on the type of spicules they

have. This is an important fact when considering the sponge

species we are attempting to keep within an aquarium setting as the

materials needed, such as silicon, will need to be present in its

dissolved form within the water in order for the sponge to create new

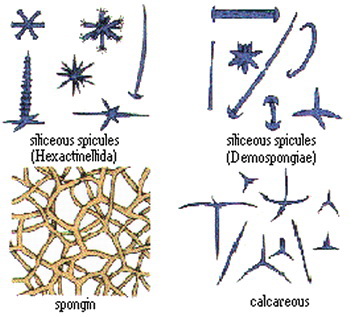

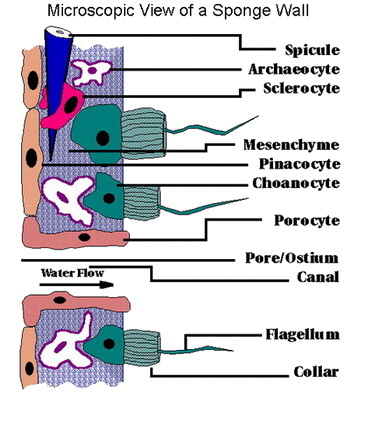

spicules needed for support during growth.  Sponges are made of four simple and independent cells. The first are

the collar cells, which line the canals in the interior of the sponge.

Flagella are attached to the ends of the cells and they help pump water

through the sponge’s body. By pumping water, they help bring

oxygen and nutrients to the sponge while also removing waste and carbon

dioxide. It is when we expose sponges to air that causes many of their

deaths during transport into our aquariums as the flagella are unable

to perform in trapped air bubbles within the sponge, kind of like

trying to row a boat by keeping the oar out of the water. Such

exposure causes the death of the surrounding cells which can lead to

necrotic tissue spreading untill all cells are affected.

Sponges are made of four simple and independent cells. The first are

the collar cells, which line the canals in the interior of the sponge.

Flagella are attached to the ends of the cells and they help pump water

through the sponge’s body. By pumping water, they help bring

oxygen and nutrients to the sponge while also removing waste and carbon

dioxide. It is when we expose sponges to air that causes many of their

deaths during transport into our aquariums as the flagella are unable

to perform in trapped air bubbles within the sponge, kind of like

trying to row a boat by keeping the oar out of the water. Such

exposure causes the death of the surrounding cells which can lead to

necrotic tissue spreading untill all cells are affected.