Sponsored in Part By

By

Charles & Linda Raabe

Mactan Island, The Philippines

© 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Mactan Island, The Philippines

© 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The vast majority of worms will prove to be harmless or at the

least, a

predator of other small worms and pose no threat to the larger life

forms that we place in our tanks. Of course there are

exceptions. While some worms can grow large

and seem threatening they are in fact a vital part of the clean up

crew, taking care of unseen livestock deaths and left over food.

It is

this clean up service that they provide that has led to some species

being labeled as fish killers as they are usually blamed for such

fish losses when they are seen on the corpse of the

fish doing their job of cleaning house.

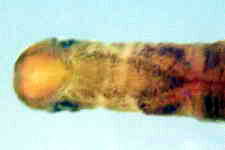

In the hopes of saving you some confusion as has happened to me quite a few times, I am showing a few examples of the rear sections of various worm species as they can be quite easily confused for the worm's head. A great many of the worms can be very lengthy and it is very common to break the worms while trying to remove them from rocks. Of course a good many times, I end up with the wrong half. To further mislead you, the worm, even though broken in half will still move its rear section in much the same manner as you would expect the head to do. Add a few false eye spots and a worm's hiney quickly becomes its head in appearance. Some species such as the Nemertea have a suction cup like appendage as a hold fast for their rear section which looks very much like a mouth and is often thrashed about as you would expect a head to do, but in reality the rear section is actually just in search of something to grasp onto.

The Nemertea ( Ribbon Worms ) Generally, nemertines are carnivorous; most feed on small invertebrates like crustaceans and annelids, but some feed on the eggs of other invertebrates, and a few live inside the mantle cavity of molluscs and feed on microbes filtered out by the host.

Below, a Baseodiscus hemprichii

Below, an unknown species

Below, a Notospermus tricuspidatus

Below, an unknown species

Below, various unknown species

The Echiura - Commonly called "Spoon worms", are considered close relatives of the Anellids but lack the segmentation of the Anellids. Most species are found in soft sediments forming burrows. The proboscis of the worm is usually the only part of the worm that we see as it gropes around for detritus and other food particles on the substrates near its burrow.

The Polynoidae - The polynoids known commonly as "scale worms" are slow moving predators which feed on small prey such as small crustaceans, echinoderms, polychaetes, gastropods, sponges and hydroids in spite of their strong jaws. They are famous for their commensal habits, some living with asteroids, echinoids, holothorians, sea anemone, sea grasses and corals. They are known as scale-worms as their dorsal surface is covered with enlarged scales or elytra which may be concealed by a dense coating of setae. They are medium sized. They are secretive and are mostly found occupying tight crevices beneath stones. Some species are commensals in the burrows and tubes of other invertebrates or the shells of hermit crabs.

Extended Jaw Details :

Below, a Harmothoinae sp.

Below: Unidentified Scaleworm

Below: A scaleworm of the Acoetidae family. Creates tubes much like the "featherdusters" do and is an active predator and scavenger. Also a large worm, the specimen shown below was as thick as my finger and at least four inches long.

The Sigalionidae - The Sigalionids are burrowing predators living in sand or mud. A few species inhabit tubes. Others have spinning glands and produce numerous tough fibers incorporated into the tubes. They are common in soft-bottoms. Being long-bodied and their scales being closely appended to the bodies, they appear rather pentagonal. Also members of the "Scaleworms".

Species below is a Euthalenessa oculata

Extended Jaw details:

The Cirratulids - Cirratulids are deposit feeders which gather food from the sea bottom by means of their palps. They are sluggish worms which bury themselves below the surface of sea bottoms leaving only their gills and palps visible. Some are free-living and inhabit tubes, while others are capable of burrowing through corals, shell or rock. Hence, they occur both in shallow water as well as deep sea. They inhabit mud flats or muddy areas between rocks. They are usually orange or bright red and are found among mussels and kelps. They are indirect deposit-feeders. They have no proboscis as their food is collected by their palps and carried to the prostomium.

Below: A hair worm hiding just under the sand's surface extending its feeding palps.

The Sipunculida Worms Article #2 - These animals, which are commonly called "peanut worms" because some have the general shape of shelled peanuts, are not particularly well studied. Only about 320 species have been formally described, all marine and mostly from shallow waters. While some burrow into sand and mud, others live in crevices in rocks, or in empty shells. Still others bore into rock.

The Priapulida Worms - The Priapulida, or Priapula are a small phylum (about 16 species known to scientists) of normally small worm like animals. They range in length from 0.5 mm for species of Tubuluchus to around 200 mm for species of Priapulus. They occur in most seas, both tropical and polar, at a variety of depths, from shallow coastal waters to as far down as 7,200 meters. The name Priapulida refers to the fact that the scientists who first named them thought they looked like a human penis, however they look more like some species of cacti and it would not be unreasonable to use the term Cactus Worms as their common name. All known species are marine and benthic (meaning they live in or on the sea floor).

THE "BRISTLE" WORMS

This is an extremely large

classification of worms, of which I will try to

post representatives of, within reason.

These

are what give the "bristle" worms their name. Each member of this

family comes armed in various rigid hair like structures that are used

for defensive means. Do not attempt to handle these worms

since

their bristles easily penetrate human skin, depending on the species

and your own personal reaction level, the resulting puncture can result

in anything from a mild irritation to being very pain full. Do not

attempt to rub them off as you will only drive the bristles in deeper.

Instead, soak the effected area in very warm vinegar until the bristles

dissolve. A thank you to David Lee for sacrificing his finger

in

the name of science!

These

are what give the "bristle" worms their name. Each member of this

family comes armed in various rigid hair like structures that are used

for defensive means. Do not attempt to handle these worms

since

their bristles easily penetrate human skin, depending on the species

and your own personal reaction level, the resulting puncture can result

in anything from a mild irritation to being very pain full. Do not

attempt to rub them off as you will only drive the bristles in deeper.

Instead, soak the effected area in very warm vinegar until the bristles

dissolve. A thank you to David Lee for sacrificing his finger

in

the name of science! The Phyllodocidae - The phyllodocids are slender errant worms often brilliant green, yellow or red. Most of them live in crevices and under stones. Active predators of other small worms. The phyllodocids are common shallow-water polychaetes commonly associated with hard substrates and corals rather than mud and sand.

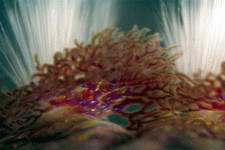

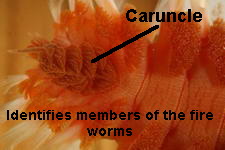

The Amphinomidae - Amphinoids are also known as "fireworms" and have calcareous setae filled with poisonous secretions. When irritated, they erect their sharp setae which break off at a touch releasing their poisonous contents into the wound. Most species are found on corals, rocks and other hard substrata covered with attached organisms. They swim well and can be brilliantly colored. All but one species can be considered harmless and are great scavengers.

Species shown below : Hermodice carunculata - This is the one species of fireworm that you do not want in your aquarium as it is a known predator of corals.

The below pictured specimen is a Pherecardia striata, also a member of the fireworms and is a scavenger.

Genus Pareurythoe , which has very small caruncles.

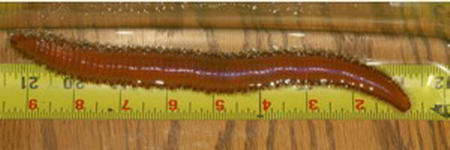

Eurythoe complanata - Probably the most commonly found worm and is a harmless scavenger, a benefit to our systems.

The Hesionidae - The hesionids are active and carnivorous. They are commonly found in hard substrates and shallow water rarely in deep water and soft sediments. The larger hesionids are carnivores feeding on polychaetes and other small invertebrates. Some may be deposit-feeders, ingesting detritus.

Below, a Leocrates spp. (member of the Hesionidae)

The Myzostomida - Quote, Leslie Harris "There's been a lot of debate about where these belong but traditionally they've been considered polychaetes. The "legs" are parapodia; each one has a stout hook (or a few) which enable them to hold onto their hosts which are usually crinoids or other echinoderms. Some are external symbionts, others are internal & can be found in galls or in the body." Unquote.

The Eunicids - The eunicids sometimes known as "rock worms" are mainly omnivores and live largely on detritus. They may be scavengers, and are found mostly in rocky habitats. Some species build tubes while others burrow into limestone. They are either errant or tubicolous frequently inhabiting coral reefs, sands and muddy substrates. These are the most commonly found worms that I encounter within live rock tunnel networks.

A Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Eunice - An excellent identification guide. Down load in .pdf format.

Some of the larger species, or those that grow to adult size in your aquarium may pose a threat to some sessile invertebrates and possibly some types of coral species. I have at least one large specimen in my aquarium and it has posed no threat to anything.

Jaw extension , and a great visual clue as to why you do not want this in your aquarium.

Below is a typical rock burrow that the larger specimens, such as the one above, will fashion by "gluing" rocks together with a mucus secretion. It is thought that these species account for new coral reef habitats as they bring together smaller rocks, thus forming a larger area that corals can settle upon, encrust and start the makings of a new reef habitat.

The Syllidae - The syllids are a large and diverse group of active worms which are mostly found creeping over sponges, ascidians, hydroids, bryozoa and algae or burrowing in the surface layers of silt and are common in protected sandbanks. They pierce the skin of these sedentary animals and pump out the juice. They are common in shallow water forms, and tend to be numerous on hard substrates and soft-bottom sediments.

Species shown in the below three photos is a member of the Amblyosyllis genus ( a Syllidae )

Syllidae SubFamily : Eusyllinae

Syllidae SubFamily : Autolytinae

Specimen shown below is about 2mm in length, a very tiny worm yet its stripes are still visible from a distance.

The Nereids (Quote, Leslie Harris ) "Carnivores, predators, scavengers, detritivores, omnivores, herbivores - pretty much every type of feeding except filter feeding & parasitism occur in the family. Many species are switch hitters. If a tasty pod is crawling by they'll grab it but if not they'll eat mud & digest the attached bacteria, detritus, etc. "

The Lumbrinerids - They are primarily soft bottom inhabitants, but can occur on hard substrates. Some construct mucus tubes. They have a well-developed jaw apparatus suitable for grasping food material. Most of them are predaceous carnivores or scavengers.

The Oenonids ( Predator of snails and clams ) - Oenonids are mostly large worms that burrow in sand and mud, but a number of species are parasitic. They resemble lumbrinerids in appearing earthworm-like, but can be distinguished from them by the presence of a flattened head.

The Glycerids - The glycerids burrow in sandy or muddy substrata by means of their reversible proboscis. The purpose of burrow construction is for prey capture. The glycerids detect the hydrostatic change within the burrow when motile polychaetes or crustaceans move across the burrow system and thus shoot out their proboscis and grab its prey. They are mainly carnivorous.

The Capitellidae - The capitellids commonly known as "lugworms" resemble the earthworms and have similar habits. They burrow in various grades of sandy mud inhabiting mucus-lined tubes. Their guts are filled with inorganic matter along with organic matter.

The Dorvilleidae - Members of this family are much smaller than most of the more larger, visible families and pose no real threat to other life in our aquariums. They will appear as very small white lines on the glass of our aquariums and are very common. Each specimen that I have examined under a microscope appears to be gut loaded with algae. While a good many species are extremely small, there are of course much larger species, some of which have been reported up to three inches long.

The species shown below is about 1 mm in length and is in the genus group Ophryotrocha

The Spintheridae - An ectoparasite of sponges. Extremely small and difficult to see when laying flat against its sponge prey. It does however leave behind its tell tale damage as shown in the below photo. Very similar in appearance to harmless Bryozoans.

POLYCHAETE REPRODUCTION

Prior to segmented release of Epitoke Free swimming Epitoke Another free swimming Epitoke

A swarming Phylodocid found within my aquarium at night. It is less than 1 mm in length but still visible as being a worm.

An Ophelidae swarmer releasing its payload.

A Unicid full of eggs releasing them

A Syllid swarmer (epitoke) in the Exogoninae genus. A male full of sperm, females carry their eggs on the outside.

Another Syllid Epitoke

carrying away (green) eggs to be released as plankton.

A Spionid epitoke, a first find for me as I have never seen a spionid outside of its tube.

Some polychaete species also form clear, gelatinous eggs masses which may become coated with detritus, cyanobacteria. Usually after a few days, the eggs will develop into worm larvae which are released after the "bubble" has disintegrated.

( Quote by Dr. Ron Shimek )

" What

we usually mistake as another worm species can very well be a modified

version of a bottom dwelling worm specialized to swim in the water for

reproduction. There are number of types of swarmers (some are called

"epitokes," some "heteronereids"). In essence the two major strategies

used seem to be:

1) Some species (primarily in the group known as the syllids) bud a whole specialized individual (a clone) off some portion of the adult. That clone is modified in having no gut, super-sized eyes, and super sized parapodia (lateral paddles). In these animals, the interior of the worm is packed with fat and other food reserves. The definitive adult deposits its fertilized eggs on the swarmer which then breaks off and swims away. As it swims, it - of course - disperses to a new habitat carrying the babies on it. Those babies develop through the embryonic stages while attached to the swarmer/swimmer. When it finally runs out of food (remember with no gut, it can't feed). It settles to the bottom, and the, now, juvenile worms can strike out on their own.

2. Another type of swarmer is formed from the entire adult which transforms itself into a swimmer in much the same manner as the one above. However, in this case, the gut degenerates and the entire inside space of the worm is filled with gametes (either sperm or eggs). When the time is right, these worms (generally in the thousands to bizillions) swarm to the surface and writhe around. In doing so, they rupture and release eggs or sperm into the water. The gametes meet, and... some time later a new worm settles out of the plankton.

3. A different rather intermediate version is seen in some of the tropical eunicids (the palolo worms, where the worm buds off a swarming portion filled with gametes. These portions swim up to the surface as in the case above. However, here instead of the whole worm committing suicide in an orgy of reproduction, only a portion of the adult participates while the portion remaining at home in the burrow regenerates and gets ready for next year. "

"

The Swarmers "

Prior to segmented release of Epitoke Free swimming Epitoke Another free swimming Epitoke

A swarming Phylodocid found within my aquarium at night. It is less than 1 mm in length but still visible as being a worm.

An Ophelidae swarmer releasing its payload.

A Unicid full of eggs releasing them

A Syllid swarmer (epitoke) in the Exogoninae genus. A male full of sperm, females carry their eggs on the outside.

A Spionid epitoke, a first find for me as I have never seen a spionid outside of its tube.

Some polychaete species also form clear, gelatinous eggs masses which may become coated with detritus, cyanobacteria. Usually after a few days, the eggs will develop into worm larvae which are released after the "bubble" has disintegrated.

( Quote by Dr. Ron Shimek )

1) Some species (primarily in the group known as the syllids) bud a whole specialized individual (a clone) off some portion of the adult. That clone is modified in having no gut, super-sized eyes, and super sized parapodia (lateral paddles). In these animals, the interior of the worm is packed with fat and other food reserves. The definitive adult deposits its fertilized eggs on the swarmer which then breaks off and swims away. As it swims, it - of course - disperses to a new habitat carrying the babies on it. Those babies develop through the embryonic stages while attached to the swarmer/swimmer. When it finally runs out of food (remember with no gut, it can't feed). It settles to the bottom, and the, now, juvenile worms can strike out on their own.

2. Another type of swarmer is formed from the entire adult which transforms itself into a swimmer in much the same manner as the one above. However, in this case, the gut degenerates and the entire inside space of the worm is filled with gametes (either sperm or eggs). When the time is right, these worms (generally in the thousands to bizillions) swarm to the surface and writhe around. In doing so, they rupture and release eggs or sperm into the water. The gametes meet, and... some time later a new worm settles out of the plankton.

3. A different rather intermediate version is seen in some of the tropical eunicids (the palolo worms, where the worm buds off a swarming portion filled with gametes. These portions swim up to the surface as in the case above. However, here instead of the whole worm committing suicide in an orgy of reproduction, only a portion of the adult participates while the portion remaining at home in the burrow regenerates and gets ready for next year. "

OF

INTEREST

While any of the below listed worms are highly unlikely to be found as hitch hikers due to their very large size, I thought they would at the least, be of interest.

The Enteropneust - (Quote Dr. Ron Shimek) " Such worms are relatively common in the sand flats around coral reefs, and are one type of animal that seems to be impossible for reef aquarists to get. They are animals that REALLY would help a sand bed in a reef tank. They are burrowing sand swallowers and are an evolutionary "half-way house" (aka "un-missing link") on the way to chordates (we'uns) from some other, possibly, wormy ancestor. They have (hundreds) of gill slits in the pharynx or throat that correspond to the gill slits in the feeding region (branchial basket) of tunicates. The gill slits also are homologous to the gill slits of fishes. They are one of the few animals in marine ecosystems that actually could use the iodine that most aquarists carelessly and foolishly dump into their systems. " Note: This specimen is now residing within my reef systems deep sand bed.

This specimen is almost three feet long Head Area Gill Area

While any of the below listed worms are highly unlikely to be found as hitch hikers due to their very large size, I thought they would at the least, be of interest.

The Enteropneust - (Quote Dr. Ron Shimek) " Such worms are relatively common in the sand flats around coral reefs, and are one type of animal that seems to be impossible for reef aquarists to get. They are animals that REALLY would help a sand bed in a reef tank. They are burrowing sand swallowers and are an evolutionary "half-way house" (aka "un-missing link") on the way to chordates (we'uns) from some other, possibly, wormy ancestor. They have (hundreds) of gill slits in the pharynx or throat that correspond to the gill slits in the feeding region (branchial basket) of tunicates. The gill slits also are homologous to the gill slits of fishes. They are one of the few animals in marine ecosystems that actually could use the iodine that most aquarists carelessly and foolishly dump into their systems. " Note: This specimen is now residing within my reef systems deep sand bed.

This specimen is almost three feet long Head Area Gill Area

THE TUBE WORMS

All

of the tube worms are harmless and may show up in large numbers usually

in high flow areas such as found in our sumps and overflows as well as

on the landscaping and some types within the sand. There is only one

type of worm that I know of that we put in our tanks on purpose, the

large tube featherduster worms, these types do have specific care needs

so please take the time to research this animal. Tube worms can come in

a large variety of sizes as well as how they structure their tubes,

even

the tubes themselves can be in a variety of shapes as well, from tiny

tight circles, to large upright tubes as well as nothing more than a

burrow in the sand with its tube formed by cementing sand particles

together to brace the walls of the sand tubing. They can also be found

living in some of the larger pores of our live rock, again, forming

mucous lined tubings such as the spaghetti worm does. The largest

family of this type of worms are the feather dusters, of which I

will try to show a few examples of. In short, if it has a feathery

looking

appendage sticking out of the end of a tube, it will be a feather

duster in general common name terms.

The Terebellidae (spaghetti worm) Tube in the sand formation Outreached feeding tentacle

Pectinaria polychaete worm

Partial Tube Removal Full Removal from Tube Head Structures

The Sabellidae with non-calcareous tubes

Below- A spionid Worm

The Serpulidae with calcareous tubes

Spirorbis Pileolaria Flabelligerid

Sand Mason Worm (Lanice) Phoronids Unknown Tube Worm

The Polyclad Flatworms, all of which are predators and not to be considered reef safe.

Below - Pseudoceros sp.

A juvenile polyclad flatworm Cestoplanidae Flatworm (polyclad) Pseudoceros leptostichus

Pseudeceros sp.(tunicate predator) Pseudocerotidae spp.

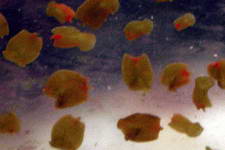

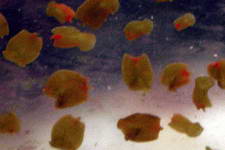

Below - Convolutriloba macropyga as identified by Dr. Thomas Shannon.

A Convolutriloba Identification Key

Feeding Mode On the move

Convolutriloba Retrogemma

Acoel Flatworm Microscopic Acoel Flatworm Below : Unidentified Acoel

Below - A Waminoea sp.

The Terebellidae (spaghetti worm) Tube in the sand formation Outreached feeding tentacle

Pectinaria polychaete worm

Partial Tube Removal Full Removal from Tube Head Structures

The Sabellidae with non-calcareous tubes

Below- A spionid Worm

The Serpulidae with calcareous tubes

Spirorbis Pileolaria Flabelligerid

Sand Mason Worm (Lanice) Phoronids Unknown Tube Worm

The Polyclad Flatworms, all of which are predators and not to be considered reef safe.

Below - Pseudoceros sp.

A juvenile polyclad flatworm Cestoplanidae Flatworm (polyclad) Pseudoceros leptostichus

Pseudeceros sp.(tunicate predator) Pseudocerotidae spp.

Below - Convolutriloba macropyga as identified by Dr. Thomas Shannon.

A Convolutriloba Identification Key

Feeding Mode On the move

Convolutriloba Retrogemma

Acoel Flatworm Microscopic Acoel Flatworm Below : Unidentified Acoel

Below - A Waminoea sp.

© 2016 ALL

RIGHTS RESERVED

All Content & Photographs are CopyRight Protected

and may not be used ,copied or reproduced elsewhere

without permission of the authors.

All Content & Photographs are CopyRight Protected

and may not be used ,copied or reproduced elsewhere

without permission of the authors.

Other good ID sites

GO

BACK

Please take a moment and

consider supporting any one of the projects listed within. Thank you.

Visitor Count as of 24 Jan.08