As with any marine species, water quality plays

an important role

in ensuring they remain healthy. Being an invertebrate, shrimp do not

tolerate anything less than reef grade water. If you can provide

consistent

water quality, you should have no trouble at all in being able to keep

your pet healthy and free of problems.

As with any marine species, water quality plays

an important role

in ensuring they remain healthy. Being an invertebrate, shrimp do not

tolerate anything less than reef grade water. If you can provide

consistent

water quality, you should have no trouble at all in being able to keep

your pet healthy and free of problems.

This may not be easy for those that do not have access to

a variety of starfish. While I have the luxury of being able to collect

any starfish myself. For those of you that have to purchase starfish in

order to feed these shrimp, you may wish to use some of the more

prolific starfish such as the common Asterina species found commonly

hitch hiking in on purchased live rock. Over the course of time, I have

collected a variety of starfish species in order to determine which are

found palatable or not, to the shrimp.

This may not be easy for those that do not have access to

a variety of starfish. While I have the luxury of being able to collect

any starfish myself. For those of you that have to purchase starfish in

order to feed these shrimp, you may wish to use some of the more

prolific starfish such as the common Asterina species found commonly

hitch hiking in on purchased live rock. Over the course of time, I have

collected a variety of starfish species in order to determine which are

found palatable or not, to the shrimp.

Depending upon their health and quality of diet, the harlequin

shrimp will molt an average of once each month. Prior to molting you

can see the exoskeleton looking like an old dirty "skin". This seems to

cause the shrimp great irritation just prior to molting. They will

constantly pick at themselves as if trying to speed up the process by

making the exoskeleton more loose by their tugging at it.

Depending upon their health and quality of diet, the harlequin

shrimp will molt an average of once each month. Prior to molting you

can see the exoskeleton looking like an old dirty "skin". This seems to

cause the shrimp great irritation just prior to molting. They will

constantly pick at themselves as if trying to speed up the process by

making the exoskeleton more loose by their tugging at it.

This only occurs directly after the female has broadcast her spawn.

Once all of the larvae have hatched, it is normal for her to molt the

next day. Once she has molted she is immediately ready to form a new

clutch of eggs, but first needs the male's contribution as the eggs are

fertilized as they pass by the deposited spermatophores. The male will

lift the female's tail and turn himself onto his back and join with the

female. It is at this time that the male applies spermatophores or

sperm sacs close to the opening of the female's genital duct. The sperm

sacs are shed from a pair of holes at the base of the last legs and the

eggs from holes on the third legs.

This only occurs directly after the female has broadcast her spawn.

Once all of the larvae have hatched, it is normal for her to molt the

next day. Once she has molted she is immediately ready to form a new

clutch of eggs, but first needs the male's contribution as the eggs are

fertilized as they pass by the deposited spermatophores. The male will

lift the female's tail and turn himself onto his back and join with the

female. It is at this time that the male applies spermatophores or

sperm sacs close to the opening of the female's genital duct. The sperm

sacs are shed from a pair of holes at the base of the last legs and the

eggs from holes on the third legs.

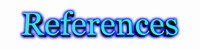

When compared to other shrimp species, the harlequin shrimp seems to

come with some extra parts, or parts that are not easily identified as

to what they are due to their flamboyant structuring. Trying to find,

let alone determine, what the various head and claw structures are can

be a bit of a challenge as the shrimp tends to shield itself, making

its smaller details difficult to see.

When compared to other shrimp species, the harlequin shrimp seems to

come with some extra parts, or parts that are not easily identified as

to what they are due to their flamboyant structuring. Trying to find,

let alone determine, what the various head and claw structures are can

be a bit of a challenge as the shrimp tends to shield itself, making

its smaller details difficult to see.

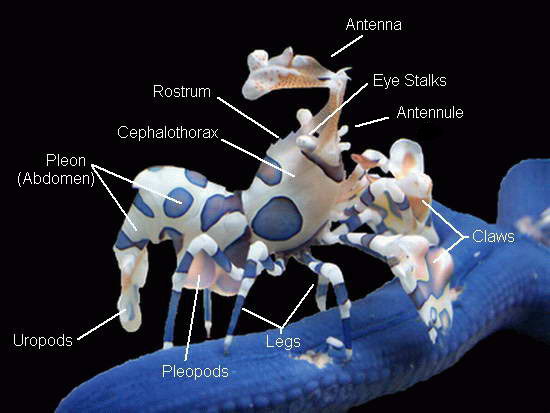

The

eyes appear to be well developed and allow the shrimp to make out

details, if the object is close enough. From a distance, they most

likely can only make out movement and the differences between light and

dark objects.

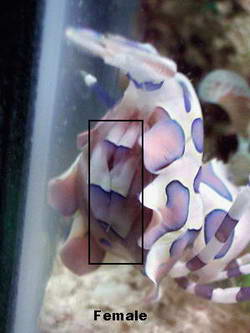

The

eyes appear to be well developed and allow the shrimp to make out

details, if the object is close enough. From a distance, they most

likely can only make out movement and the differences between light and

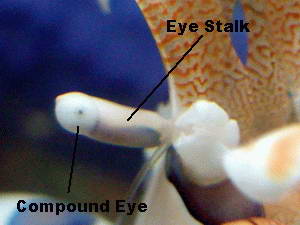

dark objects.  The mouth is not readily visible since their food particles

are

extremely small, hence no need for a large opening. The mouth can be

seen as the vertical slit shown in the photo.

The mouth is not readily visible since their food particles

are

extremely small, hence no need for a large opening. The mouth can be

seen as the vertical slit shown in the photo. The

Maxillipeds are appendages modified to function as mouth parts in some

shrimp species. I have not seen the Harlequin shrimp use them as such.

In this species they may serve more as a means to recognize friend from

foe as mated pairs often touch with their maxillae as if taste testing

each other.

The

Maxillipeds are appendages modified to function as mouth parts in some

shrimp species. I have not seen the Harlequin shrimp use them as such.

In this species they may serve more as a means to recognize friend from

foe as mated pairs often touch with their maxillae as if taste testing

each other.

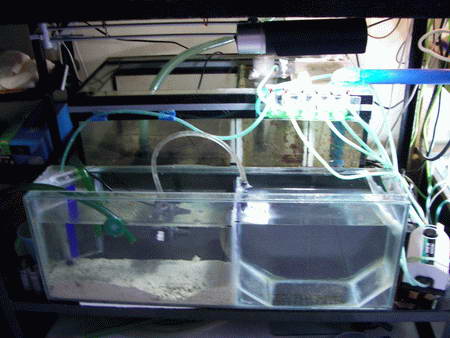

Since my wife and I live in a small apartment, I found it

necessary to limit the size and scope of my breeding program by

designing a simple, compartmented kreisel design. Such a design allows

me to keep the station near my reef aquarium. As I stated earlier, I

use water from my reef for partial water changes to the breeding

station. Of course, you can use prepared salt mixes when doing the

daily partial water changes, but I prefer to use the water from my reef

aquarium as it makes the chore a very simple matter. If you do the

same, please ensure that your reef aquarium's water is of very high

quality. Any problems with phosphate and nitrate levels will have a

very detrimental effect on the larvae.

Since my wife and I live in a small apartment, I found it

necessary to limit the size and scope of my breeding program by

designing a simple, compartmented kreisel design. Such a design allows

me to keep the station near my reef aquarium. As I stated earlier, I

use water from my reef for partial water changes to the breeding

station. Of course, you can use prepared salt mixes when doing the

daily partial water changes, but I prefer to use the water from my reef

aquarium as it makes the chore a very simple matter. If you do the

same, please ensure that your reef aquarium's water is of very high

quality. Any problems with phosphate and nitrate levels will have a

very detrimental effect on the larvae.

This is normally quite easy since in the wild mated pairs are commonly

collected and kept together to be shipped out and sold as mated pairs.

Obtaining such a pair should be a simple matter of doing an online

search or having your local store order a pair for you. If you only

need a single individual, should one of the pair die, then the store

should be able to distinguish between the sexes, allowing you to order

a male or female replacement. If the store employees do not know how to

sex the harlequin shrimp, you can describe how to do so (described

below) or you can shop elsewhere if you are not comfortable with their

ability to do so.

This is normally quite easy since in the wild mated pairs are commonly

collected and kept together to be shipped out and sold as mated pairs.

Obtaining such a pair should be a simple matter of doing an online

search or having your local store order a pair for you. If you only

need a single individual, should one of the pair die, then the store

should be able to distinguish between the sexes, allowing you to order

a male or female replacement. If the store employees do not know how to

sex the harlequin shrimp, you can describe how to do so (described

below) or you can shop elsewhere if you are not comfortable with their

ability to do so. Once

you know what to look for it is fairly easy to tell the sexes apart.

When mature, the female will appear obviously larger than the male. The

best, and most accurate method is by getting a look under their

abdomens. The male's abdomen will be clear or yellowish in color,

lacking any blue spots. The female will have obvious blue spots under

her abdomen and usually the very telling egg mass as well.

Once

you know what to look for it is fairly easy to tell the sexes apart.

When mature, the female will appear obviously larger than the male. The

best, and most accurate method is by getting a look under their

abdomens. The male's abdomen will be clear or yellowish in color,

lacking any blue spots. The female will have obvious blue spots under

her abdomen and usually the very telling egg mass as well.

While in the process of laying a new clutch of eggs, the female may go

into hiding for a day or two. I have never seen the actual egg laying

take place, yet am always happy to see her return with a new clutch of

eggs. While the female is carrying eggs, she will paddle her pleopods

quite often in order to aerate the eggs. She will also spend a good

deal of time picking at the eggs, which I assume is done to keep them

clean of any debris and to remove any unfertilized eggs.

While in the process of laying a new clutch of eggs, the female may go

into hiding for a day or two. I have never seen the actual egg laying

take place, yet am always happy to see her return with a new clutch of

eggs. While the female is carrying eggs, she will paddle her pleopods

quite often in order to aerate the eggs. She will also spend a good

deal of time picking at the eggs, which I assume is done to keep them

clean of any debris and to remove any unfertilized eggs.

When the female senses that the time is near, she will climb to the

highest point of the rock work during the middle of the night, usually

between 1:00 – 3:00 AM. I say usually, because I have had

females

broadcast their spawn at 11AM, with all the lights on, as well. During

her broadcasting, she will briskly fan her abdominal pleopods casting

her newly hatched young out into the currents.

When the female senses that the time is near, she will climb to the

highest point of the rock work during the middle of the night, usually

between 1:00 – 3:00 AM. I say usually, because I have had

females

broadcast their spawn at 11AM, with all the lights on, as well. During

her broadcasting, she will briskly fan her abdominal pleopods casting

her newly hatched young out into the currents. Another method used involves moving the female to the larval rearing

kreisel or tank to broadcast her spawn. If the kreisel has a slow flow

the female should not have to be kept contained in any manner within

the kreisel or larval rearing tank as she is quite easy to capture and

move.

Another method used involves moving the female to the larval rearing

kreisel or tank to broadcast her spawn. If the kreisel has a slow flow

the female should not have to be kept contained in any manner within

the kreisel or larval rearing tank as she is quite easy to capture and

move.

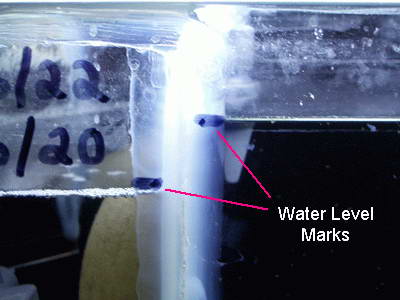

This will take some daily maintenance on your part. Your most immediate

task will involve ensuring that their water quality remains pristine.

The only way you will be able to do so is by performing small water

changes each and every day. Skip a day, and you risk losing your

larvae. Ammonia and nitrites are very deadly to the larvae. These water

changes will also be used to siphon out any and all debris that may

accumulate. I use a foot long piece of rigid tubing that is attached to

a length of airline tubing. The smaller diameter allows greater control

over what you are siphoning out and poses less of a risk of tossing the

baby out with the bathwater, as would happen with larger diameter hoses.

This will take some daily maintenance on your part. Your most immediate

task will involve ensuring that their water quality remains pristine.

The only way you will be able to do so is by performing small water

changes each and every day. Skip a day, and you risk losing your

larvae. Ammonia and nitrites are very deadly to the larvae. These water

changes will also be used to siphon out any and all debris that may

accumulate. I use a foot long piece of rigid tubing that is attached to

a length of airline tubing. The smaller diameter allows greater control

over what you are siphoning out and poses less of a risk of tossing the

baby out with the bathwater, as would happen with larger diameter hoses. After having read a few studies done with the feeding of larval shrimp,

I now only feed my larvae a cyclopoid species of copepods and only

resort to the use of brine shrimp when I am unable to collect copepods

due to the weather. In these studies, it was noted that when the larvae

are fed brine shrimp, the rate of larvae loss is extreme, upwards of 96

percent. This may explain my first poor attempts at keeping the larvae

alive long enough to settle out as I had assumed that baby brine shrimp

would be an adequate food source for the duration of the larvae

development. Harlequin larvae do not swallow food whole, they catch

food and chew on it, so food size is not very critical, although being

too small is no good as the larvae will most likely ignore small food

sources.

After having read a few studies done with the feeding of larval shrimp,

I now only feed my larvae a cyclopoid species of copepods and only

resort to the use of brine shrimp when I am unable to collect copepods

due to the weather. In these studies, it was noted that when the larvae

are fed brine shrimp, the rate of larvae loss is extreme, upwards of 96

percent. This may explain my first poor attempts at keeping the larvae

alive long enough to settle out as I had assumed that baby brine shrimp

would be an adequate food source for the duration of the larvae

development. Harlequin larvae do not swallow food whole, they catch

food and chew on it, so food size is not very critical, although being

too small is no good as the larvae will most likely ignore small food

sources.

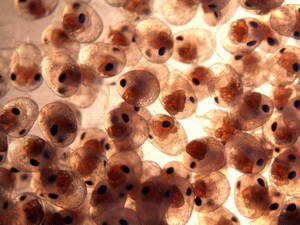

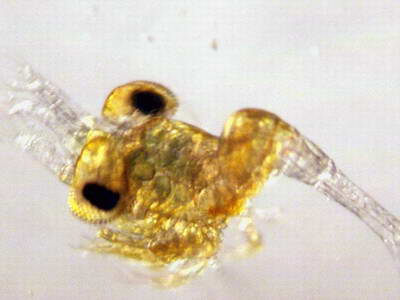

If you have access to a microscope or a quality magnifying glass, you

can remove one of the larvae every few days and watch the changes they

go through after each molt. I find it fascinating to see how after each

molt, they gain another body part or two. Do not be surprised if on

occasion you can not note any changes as shrimp larvae are known to

perform "mark time" molting which appears to be a slowing or delay

mechanism for reasons unknown. Such molting extends the length of time

the larvae remain in a specific stage of their development, which is

why it is impossible to say with certainty how long a given shrimp

species larval period will be. For the harlequin shrimp, the average is

between four to eight weeks.

If you have access to a microscope or a quality magnifying glass, you

can remove one of the larvae every few days and watch the changes they

go through after each molt. I find it fascinating to see how after each

molt, they gain another body part or two. Do not be surprised if on

occasion you can not note any changes as shrimp larvae are known to

perform "mark time" molting which appears to be a slowing or delay

mechanism for reasons unknown. Such molting extends the length of time

the larvae remain in a specific stage of their development, which is

why it is impossible to say with certainty how long a given shrimp

species larval period will be. For the harlequin shrimp, the average is

between four to eight weeks.

As you can see, this little endeavor is not for the faint hearted or

those not willing to put in the time each day. Myself, I would, and

hopefully soon, will take satisfaction in not only being

successful with breeding a marine species, but also in being able to

make the young adults available to the trade and thus take that little

bit of pressure off of the wild stocks here locally. Besides that, its

just plain fun! If you have any further questions, you can contact me

through my website and I will do my best to get you the answers to your

questions. Hopefully this article has covered enough ground to answer

the majority of them, or at the least, it got you off on the right

foot. I hope you enjoyed it!

As you can see, this little endeavor is not for the faint hearted or

those not willing to put in the time each day. Myself, I would, and

hopefully soon, will take satisfaction in not only being

successful with breeding a marine species, but also in being able to

make the young adults available to the trade and thus take that little

bit of pressure off of the wild stocks here locally. Besides that, its

just plain fun! If you have any further questions, you can contact me

through my website and I will do my best to get you the answers to your

questions. Hopefully this article has covered enough ground to answer

the majority of them, or at the least, it got you off on the right

foot. I hope you enjoyed it! I would like to thank my wife, Linda, for her continued support and

understanding while I pursue my many marine interests. A special thanks

also goes out to hobby experts, Syd Kraul of Pacific Planktonics, Eric

Borneman and Dr. Ron Shimek for their teachings and advice. I also

highly appreciate the editorial services that Carmalee Scarpitti

contributed. I can only imagine what a herculean effort it must have

been to correct my grammar and spelling, Thank you!

I would like to thank my wife, Linda, for her continued support and

understanding while I pursue my many marine interests. A special thanks

also goes out to hobby experts, Syd Kraul of Pacific Planktonics, Eric

Borneman and Dr. Ron Shimek for their teachings and advice. I also

highly appreciate the editorial services that Carmalee Scarpitti

contributed. I can only imagine what a herculean effort it must have

been to correct my grammar and spelling, Thank you!